http://www.calvin.edu/academic/cas/gpa/wehr02.htm

Background: The German army began publishing a biweekly magazine in 1937. This article is the first reporting on the German invasion of Poland. The claim is that Hitler was completely innocent, indeed that Poland had plans to take over most of Germany. The source: “Warum und wofür?,” Die Wehrmacht, 3 (1939, Nr. 19), p. 2. Why and For What?Why are we fighting? Because we were forced into it by England and its Polish friends. If the enemy had not begun the fight now, they would have within two or three years. England and France began the war in 1939 because they feared that in two or three years Germany would be militarily stronger and harder to defeat. The deepest roots of this war are in England’s old claim to rule the world, and Europe in particular. Although its homeland is relatively small, England has understood how to cleverly exploit others to expand its possessions. It controls the seas, important points along major sea routes, and the richest parts of our planet. The contrast between England itself and its overseas territories is so grotesque that England has always has a certain inferiority complex with respect to the European continent. Whenever a continental power reached a certain strength, England believed itself and its empire to be threatened. Every continental flowering made England nervous, every attempt at growth by nations wanting their place in the sun led England to take on the policeman’s role. One must understand this to make sense of England’s German policy from Bismarck to our own day. England was not happy with the results of the war of 1870-1871. British sympathies were already on France’s side, since for the previous one hundred years it had never had the same fear of France as it had of Germany. France had secured its own colonial empire, and its shrinking biological strength left enough room for expansion within its own natural boundaries. Things were different in Germany. England knew that the German people were strong when they had good leadership, and that nature had given them limited, resource-poor territory with a limited coast. Great Britain kept an eye on Germany, all the more whenever Germany expressed its strength, even in the most natural ways. The Second Reich experienced England’s “balance of power” policy. We know that England did not want a true balance of power. It wants a situation in which England is always in a position with the help of its allies to have its way with a minority of confident, forward-moving nations. England’s claims, rooted in the enormous disparity between its home territory and its overseas possessions, had to lead the English to react in bold and impudent ways in the face of a German people who under Adolf Hitler were developing their strength in an unprecedented way. In the face of the development of National Socialist Germany, England turned for a second time to a policy of encirclement, the results of which are today casting their blood-red shadow across the world. We remember its development clearly. Attempts by England and its vassals to build a ring around Germany did not have the desired results. The Western democracies made dramatic efforts to win Soviet Russia. Instead, Adolf Hitler’s hated Germany made a pact, which is founded on centuries of experience between Prussian-Germany and Russia. The Poles were the only remaining Slavic vassal in Eastern Europe. Rather than dampening the native Polish hatred of ethnic Germans and of German-Polish peace, and Poland’s desire to play the role of the big man, England did all in its power to feed the fire that was burning between Kattowitz and Danzig. Their goal was to use the situation, with the remnants of encirclement, to incite a war with Germany. The English wanted this war in the crazy hope that it was their last chance to stop Germany’s growing strength. They passionately avoided doing anything that might have prevented war. Rather than encouraging Poland to accept the Führer’s generous proposals to resolve the situation, they encouraged it to let the deadline pass, thereby providing a reason for war. The Führer felt obliged to strike back only after Polish troops had crossed the German border at several places. The German fight is a defensive fight. We fight because we were forced to fight by the insults and demands against us, because of the brutal suppression of ethnic Germans in Poland, and because of the open announcements that they would do everything in their power to strangle National Socialist Germany through military or economic means. This explanation of the German defensive struggle answers the next question: What are we fighting for? We are fighting for our most valuable possession: our freedom. We are fighting for our land and our skies. We are fighting so that our children will not be slaves of foreign rulers. That is in no way an exaggeration or empty phrase. We know the English. We know about Versailles, about the colonies England stole from us, about the Ruhr, about Golzheimer Heath, about the starvation blockade. We know that we will be slaves if we do not win and we know that the goal of England’s policy of encirclement is to subject Germany to its will. We know what that means. We all remember the days when Allied inspectors wandered around Germany. We are fighting for Germany’s freedom and for Germany’s right to be a people that has all it needs to preserve its national existence. The Führer made unprecedented offers for peace and understanding to those who are now fighting against Germany. His attempts were scornfully rejected because they wanted this fight. We are fighting for a lasting peace that will make a repetition of Versailles impossible. For two long decades, it caused an enormous, constantly bleeding wound among the ethnic Germans in the East. We are fighting to save our children from the unbearable threats of the Western democracies, driven by envy and hatred. We are fighting for a happy future in a free Germany in a peaceful Europe. [Page copyright © 1998 by Randall Bytwerk. No unauthorized reproduction. My e-mail address is available on the FAQ page.] |

Imagine that the United States were in a war with a strong and determined foe. Imagine that it had become clear to American foreign policymakers that the United States were unable to militarily defeat its enemy on its own. Suppose that those policymakers looked around for a possible ally in the war, and concluded that Great Britain was the most desirable candidate. But suppose that a major stumbling block to obtaining British participation in the war on America’s side were a strong noninterventionist sentiment among the British people and an unwillingness on the part of the members of the House of Commons to vote for entering the war as long as Great Britain was not directly under attack.

Imagine that the United States were in a war with a strong and determined foe. Imagine that it had become clear to American foreign policymakers that the United States were unable to militarily defeat its enemy on its own. Suppose that those policymakers looked around for a possible ally in the war, and concluded that Great Britain was the most desirable candidate. But suppose that a major stumbling block to obtaining British participation in the war on America’s side were a strong noninterventionist sentiment among the British people and an unwillingness on the part of the members of the House of Commons to vote for entering the war as long as Great Britain was not directly under attack.

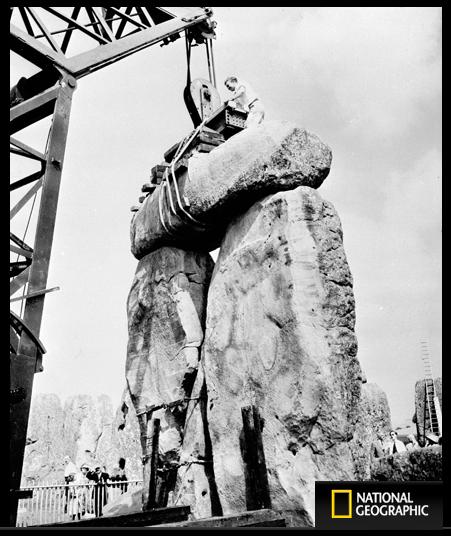

![[William_Gowland2.jpg]](http://exociencias.files.wordpress.com/2012/03/william_gowland2.jpg?w=99)