Este artículo hace eco sobre viejos comentarios que conocí en el sentido que el Káiser también repudiaba a EUA y su estilo de vida y con mucha razón, la plaga del siglo XX y XXI solo apta para lerdos sin criterio.

George Dvorsky

Nearly two decades before the onset of World War I, Kaiser Wilhelm II set his imperialistic sights on the Americas. But to establish a presence there, Germany would have to put the U.S. in its place. To that end, it devised not one, but three plans to attack and invade America. Here's how history could have unfolded very differently.

The plans for Imperial Germany's invasion of the United States only came to light after the documents were found in 2002 at the German military archives in Freiburg. It was a remarkable and disturbing discovery, one which demonstrated the extent to which the Kaiser was willing to exert Germany's presence onto the world — an urge that would continue well into the 20th century with the invasion of France in 1914 and the rise of Hitler's Third Reich.

Late to the Show

Germany was a latecomer to the world scene by the time the 19th century came to a close. The country only came into existence in 1871 when its various provinces were unified at the conclusion of the Franco-Prussian War. At the time, Chancellor Otto von Bismarck adopted a policy of Realpolitik. It was a practical means to position Germany as a mediator of European affairs. But it was a policy that wasn't meant to last; soon after Kaiser Wilhelm II took over, the young nation became feverishly nationalistic, adopting the militarily aggressive and opportunistic Weltpolitik as way to expand the German Empire into a world power.

Expand

ExpandAs noted by German Foreign Secretary Bernhard von Bulow in a statement to the Reichstag in 1897, "[In] one word: We wish to throw no one into the shade, but we demand our own place in the sun." Indeed, the upstart nation was jealous at the success of its rivals, namely Britain, France, and the United States.

Expand

ExpandGerman colonies prior to the onset of World War I. Compared to Britain and France, a drop in the bucket. Credit: Creative Commons.

As for the USA, it had adopted the Monroe Doctrine some 50 years earlier — a policy aimed at curbing European colonial ambitions in North, Central, and South America.

It was the combination of these two foreign policies that nearly led to a cataclysmic conflagration along the Eastern seaboard of the U.S. at the dawn of the 20th century. The Kaiser, intent on defying the Monroe Doctrine, had plans to set up a major naval Caribbean base in Cuba or Puerto Rico. From there, Germany could have access to South America, Central America, and the Panama Canal, which it planned on taking over once complete. Germany was clearly thinking big; it wanted nothing less than unhindered access to the Pacific Ocean.

But to achieve these goals, Germany would have to deal with the United States. To that end, Kaiser Wilhelm II had his military thinkers sketch out plans to attack and invade the American mainland. The intent was never to take over the U.S., but rather to force the country's leaders to bargain from a weak position.

Plan I: Attack and Blockade

Germany's first plan, which was devised by Naval Lieutenant Eberhard von Mantey in 1898, was a scheme to attack U.S. naval power on its east coast in order to gain easy access to a planned German naval base in the Caribbean.

Expand

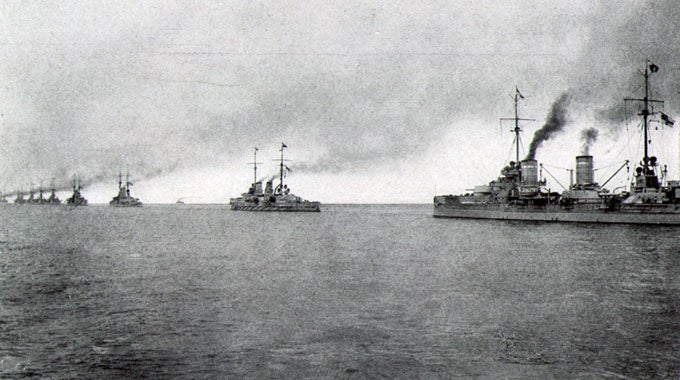

Expand The scheme would have seen a great German fleet to sail across the Atlantic to engage and defeat the U.S. Navy's Atlantic Fleet in a major battle. In addition, German naval artillery attacks were to be directed on the Norfolk Naval Shipyard, the Newport News Shipbuilding center, and other naval resources in the Hampton Roads area of Virginia. Lieutenant von Mantey believed this was the "most sensitive point" of American defenses, and once reduced, would have allowed the Germans to establish a naval blockade. At that point a German negotiating team would have been sent in armed with with the Kaiser's demands.

But this plan was never meant to be. Germany simply didn't have the required ships. What's more, the start of the Spanish-American War resulted in increased American activity in the Caribbean, along with the establishment of a (soon-to-be) independent Cuba under American economic influence.

Plan II: Land Invasion

If the first plan wasn't ambitious enough, the Kaiser's second plan certainly made up for it. The Kaiser had von Mantey revise the scheme in 1899 — but this time he had to provision for a two-pronged land invasion of New York City and Boston. The unprecedented invasion would have required 60 warships and a massive supply chain of at least 60 cargo and troopships carrying 75,000 tons of coal, 100,000 soldiers, and a large amount of artillery. The invasion force would have required 25 days to cross the Atlantic.

Here's how it would have unfolded: After a major naval battle to acquire superiority over American ships, German troops — armed with artillery — were to make an amphibious landing at Cape Cod. These grounds units would then advance to Boston and fire shells into the city. For its attack on New York, German troops were to land on the island of Sandy Hook, New Jersey, while warships pounded away at harbor fortifications, including Fort Hamilton and Fort Tompkins. Following this, the warships would advance to shell Manhattan and other areas of New York in an effort to induce panic among civilians. It would have been absolute pandemonium.

Image: The remains of Fort Tompkins in New York.

Alfred von Schlieffen, the author of the famous World War I plan that bore his name, refused to believe that such a plan would work. It would take a lot more, he argued, to take a city like New York, a metropolis that boasted some 3 million people.

By 1900, the Kaiser realized that an invasion force launched from Germany was unfeasible. He once again set his sights on a land base in Cuba from which such an invasion could be launched.

Related: The 10 Biggest Misconceptions About the First World War | How Each Of The Great Powers Helped Start the First World War

Plan III: Variations on a Theme

From 1902 to 1903, German planners, including naval staff officer Wilhelm Büchsel, made minor changes to their tactics. But this time they took global politics into consideration. Seeking to gain a political advantage, they sought to establish a naval base in Culebra, Puerto Rico from where they could threaten the Panama Canal.

At the same time, however, Germany did not waiver from its initial strategy of seeking to immobilize the United States. As von Mantey noted in his diary, the "East Coast is the heart of the United States and this is where she is most vulnerable. New York will panic at the prospect of bombardment. By hitting her here we can force America to negotiate."

A Different Course of History

But world events would preclude Germany from ever embarking on such schemes. An invasion of the United States would have only been feasible if two conditions were met: (1) the absence of a major conflict in Europe and (2) an unprepared United States. By the first decade of the 20th century, these variables were withering away.

First, with the advent of the Entente Cordiale by Britain and France and the subsequent shifting of power in Europe, Germany suddenly had other things to worry about. Now best-buddies, Britain and France could shift their forces elsewhere — much to the chagrin of the Kaiser. Compounding this was Germany's inability to leapfrog ahead of Britain in the naval arms race of the time.

Expand

ExpandMeanwhile, the United States began to assert itself in its part of the world. The Venezuela Crisis of 1902-03 demonstrated that the U.S. was willing to use its naval strength to impose its viewpoint on the world — a crisis that led to President Theodore Roosevelt's "Roosevelt Corollary" to the Monroe Doctrine, a policy whereby the U.S. made its intentions clear to intervene in conflicts between European and Latin American countries (a policy that positioned the U.S. as a "police power" — the reverberations of which are still being felt today).

What Could Have Been

Despite the seriousness of the Kaiser's planning, it's doubtful his scheme would have worked under any incarnation. As noted, the Imperial German Navy was ill-equipped to pull off such a stunt, even if did manage to establish a base in the Caribbean. What's more, incursions into the region would have put America on red alert, so a surprise attack would have been unlikely. In fact, the American navy would have likely confronted German forces before any kind of troop build-up could occur on Cuba, Puerto Rico, or elsewhere (the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 most certainly comes to mind).

Additionally, had Germany launched its attack on New York City and Boston, it's unlikely that Theodore Roosevelt would have been forced into a negotiating position; he would have likely refrained from speaking softly, while brandishing his proverbial big stick. With German forces 4,000 miles from home, and with the mass of the United States ready to defend itself, such an incursion would have been easily repulsed.

Sources: Zeit Online | The First World War (BBC, 2003) | European istory

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario